Songs of Protest: Tropicália and Countercultural Music in 1960s Brazil

The short-lived — yet still thoroughly pioneering — Tropicália movement of the 1960s challenged Brazil’s military dictatorship through carefully-cultivated music rooted in defiance and eagerness for change.

Music is one of society’s best teachers. In Songs of Protest, writers analyze some of music’s greatest hits, using their findings to make sense of the world around them.

Written by William Golden

Image courtesy of UMG

The 1960s was a time of worldwide protest. Although anti-war and anti-government demonstrations in the United States and Europe received a lot of coverage, Brazil’s struggles are less familiar to most. In 1964, Brazil’s military overthrew the democratically-elected president João Goulart in a U.S.-backed coup. The regime suspended habeas corpus, dissolved Congress, and tortured and killed political opponents. The government’s strict censorship laws made it difficult for artists to debut original material, yet artistic expression managed to flourish.

One of the most effective forms of protest against the dictatorship was Tropicália, a movement that used art, literature, and music to deliver an anti-authoritarian message. The musical aspect of Tropicália was spearheaded by Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil, two songwriters from the state of Bahia. The change campaign took inspiration from Oswald de Andrade’s “Cannibal Manifesto,” which advocated for “cannibalizing” foreign cultural influences and making them into something distinctly Brazilian. Tropicália musicians followed de Andrade’s suggestion by combining traditional Brazilian music with psychedelic rock by groups such as The Beatles and avant-garde composers like Karlheinz Stockhausen. The result was a melding of local and international influences, ultimately creating an entirely unique style of music.

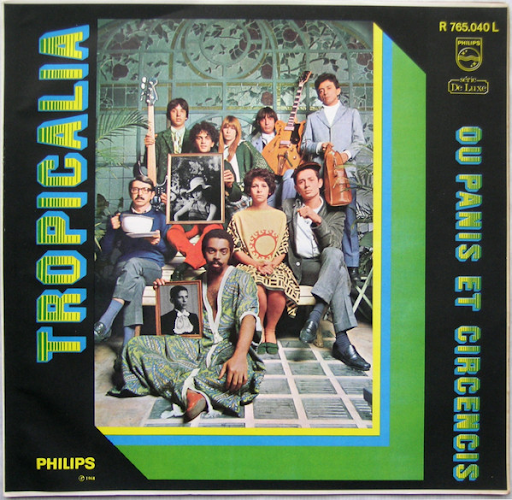

The collaborative album Tropicália ou Panis et Circencis showcases many of the musicians integral to the movement. The title references a quote by ancient Roman poet Horace about “bread and circuses” pacifying the populace while turning a blind eye to politics. Its cover, which looks like a cross between the front of The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and a family photograph, depicts many of the movement’s key figures. Gilberto Gil is seated at the front, holding a picture of the lyricist Capinam. The woman in the yellow dress is Gal Costa, a longtime collaborator of Gil and Veloso who performed four songs on the album. The poet Torquato Neto, who contributed many lyrics to his fellow artists before his 1972 suicide, is seated to Costa’s left. Rogério Duprat, who is responsible for the album’s florid arrangements, is holding a chamber pot like a tea cup on the left. At the back, Tom Zé holds a guitar alongside the members of Os Mutantes, and Caetano Veloso holds a picture of Nara Leão, who performed traditional bossa nova before turning to politically-conscious tropicalismo music.

Image courtesy of Philips Records

The opening track “Miserere Nobis” begins with the brass hums of a church organ before the ringing of a bicycle bell abruptly interrupts it. The track starts out with a blast of brass fanfare, before abruptly cutting to a hazy burst of psychedelia accompanied by tambourine shakes and singer Rita Lee’s repetitive “la-la-la”s. The rest of the song emulates contemporary British rock. Vocalist Gilberto Gil sings, “Miserere Nobis [Have mercy on us],” a Latin phrase often recited during mass, which is followed by the phrase “É no sempre será [This is how it will always be],” The song is a likely dig at the oppressive Catholic Church, but the playful instrumentation and ambiguity of the lyrics were designed to get past government censors.

The government was not the only group to oppose the music. Right-wing protestors opposed their avant-garde stylings. On the other hand, leftists did not like the adoption of foreign elements and the seeming apoliticism of many of the lyrics. Tensions between the artists and their detractors came to a head at the International Song Festival in Rio. Veloso and Os Mutantes performed the song “É proibido proibir [It is Forbidden to Forbid],” the title of which is taken from a slogan used during the student protests against the government in France in May 1968. The studio version of the song opens with a menacing two-note piano riff while bongos are hit, cymbals crash, and Veloso breathes deeply into the microphone. It then transitions into a more traditional rock song in a major key, but the lyrics contain a description of burning cars and an exhortation to “Demolish the shelves / The bookcases, the windows,” an atypical and fearlessly violent rebuke of the current regime. The song ends at a rapid tempo, with screaming voices over wailing guitars, in a sound not too far from what The Velvet Underground released earlier that year on White Light/White Heat. The experimental music and political messaging incensed many of the students in the audience, who threw debris at the performers.

The movement came to an end in December 1968, after Veloso and Gil were arrested without trial, imprisoned for two months, and placed under house arrest for four more. In an interview, Veloso claimed the regime did not “seem to be able to stand anything open-ended, anything they cannot force or control.” Both musicians were exiled from the country, leading to them spending time in London. Veloso took influence from the forward-thinking rock of groups like The Who and Pink Floyd, while Gil was entranced by the emerging reggae scene.

Photos courtesy of The Guardian and Columbia Daily Tribune

Finally, after three long years away from their home country, Gil and Veloso were allowed to return to Brazil in 1972. Incredibly, Veloso, Gil, Costa, and all three members of Os Mutantes are all still active and making music in Brazil, nearly 55 years after Tropicália’s heyday. Gilberto Gil even became a successful politician, serving as a minister in president Lula da Silva’s cabinet in the 2000s. In 2022, Veloso’s advocacy for justice continued after he led a protest opposing a series of bills that, if passed, would speed up the deforestation of the Amazon rainforest and threaten the land of many indigenous Brazilians. In an interview with The New Yorker, Veloso claimed living under the current government “feels bad, even as bad as the dictatorship, but it’s a totally different situation. One thing is certain: the people in power are nostalgic for a military dictatorship.”

Newer artists that have created their own music in protest of the current regime also take cues from their predecessors. Hip hop superstars like Emicida and MV Bill have released music highly critical of Bolsonaro. The latter’s most recent album, Voiando Baixo (Flying Low), calls out Bolsonaro’s refusal to take the pandemic seriously and the poor conditions of Brazil’s favela neighborhoods. In a concert of the politically-charged samba group Samba do Trabalhador documented in The Guardian, attendees chanted “Fora Bolsonaro!” (“Bolsonaro out!”) and wear T-shirts supporting Lula da Silva, the former president and Bolsonaro’s opponent in the upcoming election. The band chose to end the concert with a performance of a Chico Buarque song written in 1970 in opposition to the military government. Although the music might be 50 years old, its message is as relevant as ever.