TV Girl and the Nice Guy Perspective in Music

Many often ridicule the “Nice Guy” phenomenon, but entitled attitudes toward women aren’t uncommon in music. TV Girl’s “Louise” and “Hate Yourself” are great examples, with lyrics that villainize women who won’t give them the time of day.

Written by Sydney Meier

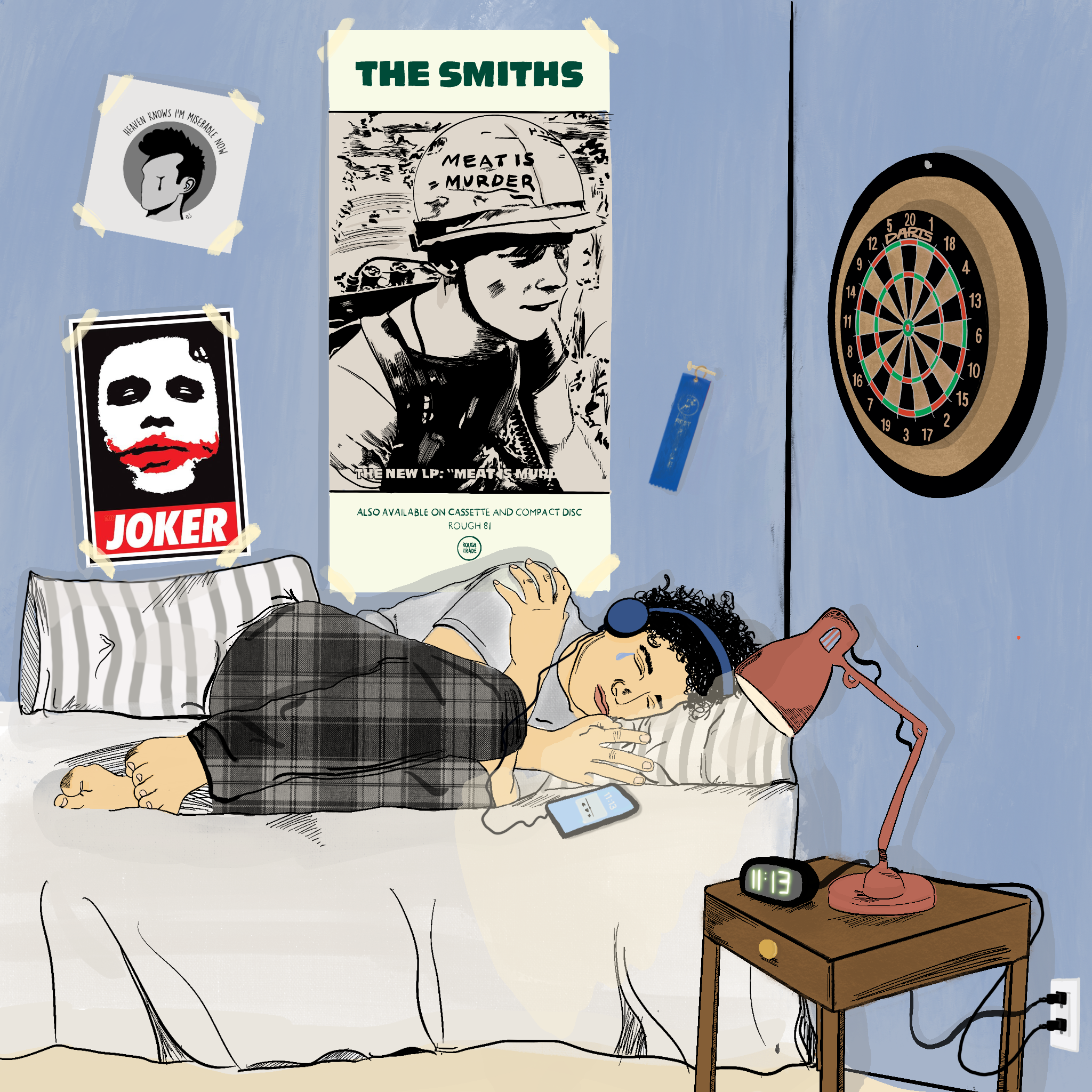

Illustrated by Alyssa Sheldon

The “Nice Guy,” in 2010s lingo, alludes to a man who consistently has ulterior motives when interacting with someone whom they are sexually attracted to. The Nice Guy believes that because they behave in a supposedly honorable way, women owe them for their so-called “kindness” towards others.

On social media, the Nice Guy might post videos or photos with captions containing his thoughts on why women deserve basic rights, or should not be brutally assaulted when just simply walking around late at night. While the sentiment seems courteous, sometimes it’s clear from the way they frame these posts that they made them with the hopes of female praise and reward for doing the bare minimum. Others might go further, posting overtly misogynistic content objectifying women — content that is tinged with the idea that men are entitled to sexual favors for treating women with basic human decency.

In music specifically, the Nice Guy is typically the narrator of the song looking back at a relationship with a woman or peeking into a relationship between another man and woman. There is usually some resentment towards the woman, either for choosing someone else, leaving the narrator, or never noticing the narrator in the first place. Some examples of the Nice Guy in music are “Jessie’s Girl” by Rick Springfield, “Let Me Love You” by Mario, and more recently, “Louise” and “Hate Yourself” by TV Girl.

Consisting of Brad Petering, Jason Wyman, and Wyatt Harmon, TV Girl started in 2010 and is still going strong in 2022. The band’s song “Not Allowed” blew up on social media around fall of 2020, listeners becoming enamored with the group’s laidback sense of style in monotone verses paired with sporadic instrumentals. The band gained such an exponential amount of popularity that it was able to tour for its debut album French Exit’s six-and-a-half year anniversary. However, what goes up must come down. This observation is not so much concerning TV Girl’s popularity but its new audience coming to the realization that the lyrics the beloved band wrote are steeped in male chauvinism. Although the artists themselves might not be writing from their personal perspective, the protagonists of these songs promote the idea that women are to blame for their lack of relationship success, not themselves. There are two specific songs by TV Girl that exemplify this: “Hate Yourself” and “Louise.”

“Louise,” the third song off French Exit, is sung from an outside perspective looking into the actions of a French woman in a love triangle with two American best friends. For the first verse of the song, the narrator villanizes Louise for being sexually active with but emotionally stagnant towards these men: “Louise she just wasn’t thinking / When she climbed into his bed / She only wanted to lie beside him / To hell with his best friend.” However, the protagonist of the song then lets his bias towards her slip, singing, “Louise / I’ll love you ‘til I’m dead.” The implication is that the real reason the speaker hates Louise is that she is not romantically interacting with or interested in him. He is inclined to jealousy towards the men as well as resentment towards Louise for not paying more attention to him.

During the second verse, the narrator goes deeper into Louise’s motivation for her playboy actions, stating that “in France” no one “heard about puppy love.” It sounds almost as if the narrator is implying Louise never received this adoring affection in France, so she never learned to reciprocate those feelings. Even though Louise is given a character explanation, the protagonist does not see this as an excuse or a reason to sympathize with Louise. Additionally, it’s notable that the narrator’s criticism focuses more on Louise than the men she is seeing. The fact that she becomes the sole subject of blame is suggestive of a misogynistic looking glass with which the narrator views the world.

Similar to ”Louise,” “Hate Yourself,” the fourth entry on TV Girl’s debut album French Exit, is sung from the perspective of an omniscient narrator, detailing the feelings and actions of a young woman who grievously hates herself. The young woman looks for self-love through validation from others, whether it be about her physical appearance or personality, with the narrator noting “I think you’d fall in love with anyone / Who fell in love with you.” Afraid of being alone with her thoughts or “locked inside'' her “room,” she jumps from relationship to relationship in the hopes of finding someone who loves her so much she might start to love herself. Once again, the narrator is in the midst of an unrequited love with the young woman whom he speaks so harshly about: “And I’ll just wait / ‘Til those arms belong to me.” The young woman receives constant romantic attention from everyone around her, but this is never enough for her to truly start seeing what the entire world sees her as.

However, the narrator does not sense this nuance within the girl’s insecurities and instead makes her out to be an undeserving recipient of this spotlight, even though he places her on the same pedestal. The narrator blames the young woman for her tumultuous relationships, singing, “But you’re the one who brought ‘em here / You’re the one who has to take ‘em when you leave.” She is the one who started and ended these relationships, so the narrator believes she is the only one who should leave with guilt. A young woman who is drowning within her own faults and failures who can’t seem to understand that validation cannot replace self-confidence, and who is so swept up within the public’s perception of her, is portrayed as nothing more than an unappreciative and unworthy woman. In turn, the narrator and others place their love upon her again and again in the hopes of molding her into something she is not and can never be without self-reflection and improvement. Yet, TV Girl is still able to drown out the narrator's sexist prejudice with staccato piano chords and mesmerizing background vocals.

The problem with the Nice Guy perspective from which TV Girl expresses its songs is there are many men who relate to this mindset, and listening to this music will only validate their thoughts. Songs like “Louise” and “Hate Yourself” reaffirm to the Nice Guy that if women do not accept their advances, it's not an issue within themselves, but with the women they are pursuing. Although there’s no harm in enjoying TV Girl’s music, impressionable listeners should know what they are getting into before delving into a discography filled with lyrics that might validate their unhealthy entitlement as to why their love interest might not reciprocate their romantic affection.