Media and Music: How Classical Music Creates an Atmosphere of Psychological Disturbia in A Clockwork Orange

Stanley Kubrick’s seminal work “A Clockwork Orange” fascinates and horrifies audiences across decades, but remains monumental in terms of masterful filmmaking and artistic, detailed soundtrack.

Written by Kaileen Rooks

Photo courtesy of The American Cinematographer

Content Warning: This article contains references to physical and sexual violence and suicide.

Like seemingly all great filmmakers, Stanley Kubrick deals heavily with violence. Kubrick clearly has a fascination with violence, yes, but this obsession is undercut by the psychological nature of his films and the careful balance of delivering a message without imposing a decisive answer on his audience. Kubrick strays from the pulp violence employed by later filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino and opts for an almost psychedelic, surreal quality intertwined with larger insights on reality. “A Clockwork Orange” is perhaps the best example from his filmography of this delicate balance, and it is done primarily through the soundtrack. The 1971 classic is one of the earliest movies to deploy the oh-so-beloved trope of layering classical music over violent scenes, arguably enshrining the use of it in popular culture and the film industry.

The film was based on a novella by Anthony Burgess, and it mostly sticks to that source material, right down to the futuristic slang used by Alex and his gang as they execute violent shenanigans in a dystopian London. “A Clockwork Orange” is a violent and disturbing film, so much so that the title became a euphemism in ‘70s England for teen crime and general deviancy. That being said, gratuitous violence is not without reason. Kubrick follows the original book almost to a T, including its core themes about society and violence itself, up until the very end. Kubrick intentionally leaves out Burgess’ controversial British ending to the novel, where the main character eventually grows out of his violent ways.

Kubrick explores this subject in a multitude of ways — from set design to shooting techniques to costuming — but none of these were quite so impactful as the film’s sound design and soundtrack. To create the complex and surreal soundscape for this film, Kubrick hired composer Wendy Carlos, who had previously become successful for her synthesized classical music adaptations like Switched-On Bach. Carlos would go on to compose the music for Kubrick’s most famous film, “The Shining,” about nine years after the release of “A Clockwork Orange.” Despite “The Shining” having marginally greater critical and audience success, “A Clockwork Orange” laid the groundwork for a score of future horror and psychological movies and is revered for its mastery of intertwining sound with the themes of the movie and facets of the plot.

The soundscape Carlos creates is nightmarish, foreboding, and unearthly. Juxtaposed with the traditional classical music used in the film, Carlos’ compositions take the audience on a whirlwind ride, vacillating between hysteria, confusion, horror, and a sense of dark ridiculousness. The electronic compositions contrast with the traditional orchestral movements implemented throughout the film. Following the turns of the plot, the orchestral movements take on different meanings throughout. Nevertheless, they rely on the structure of contrapuntal music, meaning that the music contradicts the actions shown on screen.

“A Clockwork Orange” begins with what is perhaps one of the most famous movie openings in history. The title theme is a reworked, synth-laden version of Henry Purcell’s “Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary,” produced by Carlos. The opening shot focuses entirely on our main character’s face, decorated with the infamous “Kubrick stare,” denoting evil and psychopathy. Carlos’ rendition takes a dark, psychological spin on a traditionally somber composition, befitting the music’s original woeful lyrics. "In the midst of life we are in death,” the original soprano bemoans, and Carlos’ instrumental composition matches accordingly, seamlessly blending Alex’s innate evil with skillful, understated foreshadowing of his incoming suffering.

The following half of the movie takes the audience on an odyssey of Alex’s deranged and violent lifestyle. As he violently assaults an unsuspecting old man and engages in a calamitous gang fight, an overture from the 19th-century opera “The Thieving Magpie” blares in the background, adding an equally whimsical and horrifying edge to the disturbing scenes. Kubrick then introduces Alex’s unnatural obsession with classical music, specifically Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, as a plot device that not only develops the intricacies of the main character but also sets up the movie’s heel-face turn in its latter half. As Alex listens to the second movement, the film begins one of its recurring trends where the audience gets a look inside at Alex’s internal fantasies. He pictures hangings, explosions, and images of himself as a ravenous vampire, all while the symphony’s fourth movement crescendoes dramatically in the background. The filming strategies and overlaid music in this sequence puts the audience in a voyeuristic position, caught between the wild exhilaration of the fast-paced scenes, quick cuts, and the natural revulsion that follows Alex and his droogs’ disturbed behavior, with the masterful soundtrack enhancing the film’s overall sense of psychological distress .

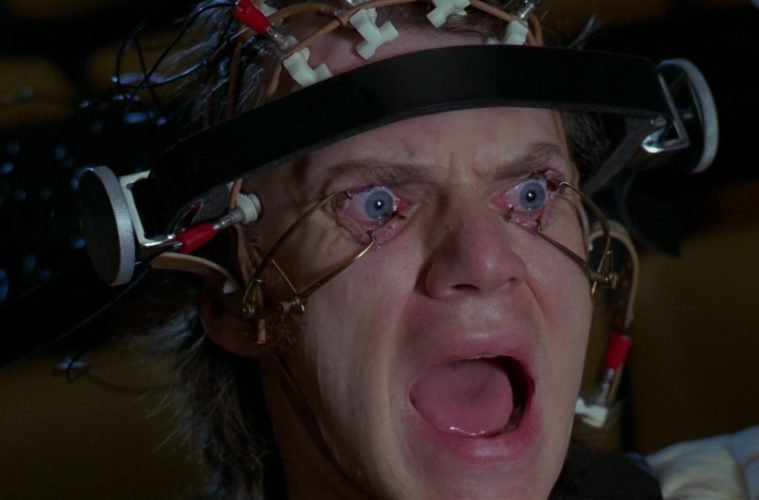

Photo courtesy of The Film Stage

Kubrick’s vortex of unnecessary violence and savage recklessness threatens to drag the audience down into a whirlpool of sadism and cruelty, culminating in Alex invading the home of and accidentally murdering an older woman while trying to rob her home. Rossini’s “La Gazza Ladra” overture roars in the background, but is quickly silenced when Alex is betrayed by his gang and promptly sent to jail. Rare moments of dialogue with no music are peppered throughout the film, adding to the eerie suspense as the audience anticipates the music’s return, simultaneously signaling the return of the movie’s interplay with horror and psychological torture. This particular moment in the movie signifies the turning of the plot. Alex becomes a subject for an unnatural technique supported by the dystopian English government known as the Ludovico Technique, a name which references Ludwig Van Beethoven. Pictured above, the aversion therapy technique forces Alex to watch various violent films, all the while under the influence of nausea-inducing drugs. Kubrick includes two different sessions of this psychological torture, with the first session overlaying Carlos’ “Timesteps,” a hazy, hair-raising track that adds to the scene’s themes of psychological warfare and torment. Alex’s second session, however, is overlaid with his favorite musical movement, a synthesized version of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony interpreted by Carlos. This moment represents the shifting purpose of classical music within the film, previously engendering dark hilarity mixed with utter brutality and now representing psychological disturbia and encroaching dread.

In the film’s second half, classical music takes a backseat to Carlos’ electronic compositions. Alex’s transformation and new aversion to violence is explored through various scenes of humiliation, degradation, and suffering. The latter half of the film relies heavily on two central pieces of music: Carlos’ Title Theme and Beethoven’s Ninth. After Alex is kicked out of his home, beaten by his former friends, and drugged by the old man he attacked in the film’s beginning, he is trapped and forced to listen to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, formerly his favorite song, causing him to attempt suicide. Alex is then trapped by political activists who intend to use his suicide attempt as a justification for their protest of the Ludovico Technique. They force him to listen to a version of Beethoven’s Ninth, performed by Carlos, driving him to hysteria and paralleling the garish crescendoes of the synths. Alex’s attempted suicide directly juxtaposes his former obsession with classical music. Previously, the Ninth conjured up images of glorious violence and debauchery — now, it sends him into a spiral of delirium and agitation. By using Carlos’ rendition in this scene, Kubrick expertly combines both sides of the movie’s soundscape into one, blending frenzy with torment.

The film concludes with a grand yet bleak overture. Alex is miraculously “cured” from his Ludovico-induced revulsion for savagery, returning to his former violent, grotesque ways. Kubrick depicts Alex’s return to “a bit of the old ultraviolence” with a flourish of the Ninth’s Finale, the scene depicting Alex raping a young woman while a crowd of well-dressed onlookers clap along. Thus, Alex’s pre-Ludovico revelry in violence and cruelty replaces his former conditioning that induced sickness and agony when hearing the Ninth or engaging in brutality. Kubrick also opts to stick to the American ending of the novel, where Alex is “cured” in the sense of becoming his former self again, rather than being “cured” of his violence altogether. Returning to his tried-and-true strategy of layering classical music over distressing and disturbing scenes, “A Clockwork Orange”’s final scene uses Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony to demonstrate the full-circle path of Alex’s progression. His throes with suffering, torture, pain, torment, and woe, were all for naught.

“A Clockwork Orange” is timeless for its nuanced commentary on free will and intricate yet seamless integration of classical music with electronic compositions. Kubrick’s skilled weaving of psychological dread paired with disturbing ridiculousness makes the perfect pairing for Carlos’ delicately crafted soundscape that relies on rippling, foreboding synths and dramatic classical flourishes. The resulting effect is a frightfully moving piece of media, one that will continue to inspire filmmakers and overwhelm audiences for years to come.