For Whom the Bags Toll: The Debut of Bagpipes in Rock Music

As they were dragged from the Scottish Highlands onto the global rock stage, the bagpipes found themselves caught in a frenzy of musical history. Rather than kilts and rolling grassland, the instrument would come to be surrounded by drum sets and guitars in the ‘70s and ‘80s, exemplifying the epochal desire to do the not-yet-done.

Written by Veronica Martin

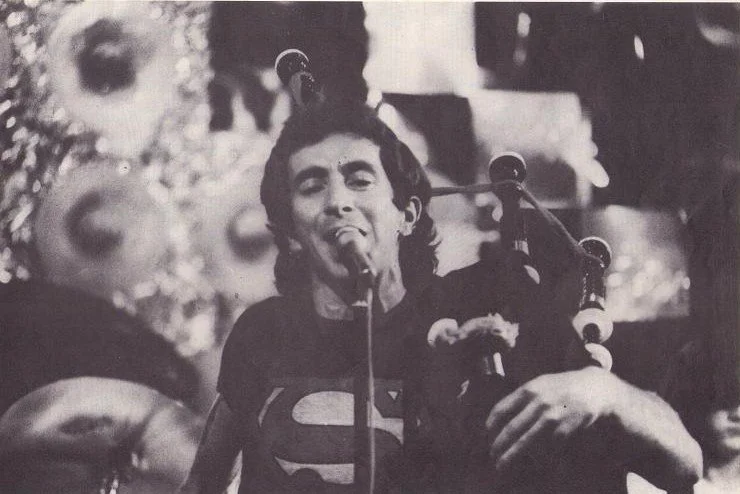

Photo courtesy of Highway to ACDC

For many, 1000 BCE is notable as the onset of the Iron Age. For some, it was the development of the Phoenician alphabet. For others, it was the debut of the bagpipes.

The sheepskin contraption has been defined over centuries as the poster child for Scottish Highland culture, though bagpipes are mentioned bountifully over countless regions throughout history — Sumeria, Persia, Greece, Rome, and even India. With humble origins as the instrument of herdsmen, being that this group had the greatest access to necessary materials such as goat skin and reed pipes, the bagpipes scaled the social ladder, later even finding themselves being the music of the royal court. King Henry VIII became the royal bagpipe buff, collecting thousands of extravagant instruments, of which included his posh ‘pipes clad in purple velvet and with ivory reeds. However, the seeds that sowed their prominence were soon reaped in their fall. With the development of Western classical music and newer instrumental technology, the bagpipes lessened in popularity as connoisseurs confronted the impracticality of their size, limited range, and rare function. It wasn’t until the 1960s that bagpipes made their striking appearances in non-ceremonial contexts. Come the ‘60s and ‘70s, new artists would incorporate the bagpipes into places they had never been in before: rock.

In 1975, Australian rock band AC/DC made music history. After bandmates learned of lead singer Bon Scott’s Irish descent, band members accused him of having been in a piping band at some point during his youth. Quickly discovering that this was false upon him failing to properly configure a bagpipe he had spontaneously bought down the street at the time, the band insisted on using the instrument on its next track anyway. Thus, “It’s a Long Way to the Top” was born. AC/DC takes an eccentric approach in the fast-paced, high-energy ode to Scott’s Irish descent. Towards the middle, the bagpipes make their grand entrance by blending in with the surrounding screeches of electric guitar, being almost inextricable from the band’s backing melodies. The solo is not only quite lengthy — occupying nearly three full minutes of the five-minute song — but dually attempts to imitate the long cries of a typical guitar solo. Rather than a multi-note melodic interjection, the solo consists mostly of prolonged shrieks from the pipes. The band’s beguiling interpretation became a hallmark example of unconventionally using unconventional instruments. That is, Scott turns the bagpipe on its head, morphing its provincial Highland-ness into an upbeat, dynamic fusion of folk and hard rock. While entirely spontaneous and somewhat facetious, AC/DC’s few and far between performances of “It’s a Long Way to the Top” reclaimed the instrument that was otherwise deemed musically obsolete.

Wings’ 1978 “Mull of Kintyre” does the exact opposite: The song pays tribute to Scotland’s Kintyre peninsula, where Paul McCartney’s farm estate lies. In fact, McCartney even employed the accompaniment of Kintyre’s local Campbelltown Pipe Band to do the supporting bagpipe playing. “Mull of Kintyre” is a Highland anthem, whereby the band drags the listener along a soft mumbly journey through rural Scotland. Like a berceuse, the serene vocals and lyrics lull the listener with visions of Kintyre: “Oh, mist rolling in from the sea” and “Dark distant mountains with valleys of green.” As opposed to AC/DC’s lively account, Wings takes an approach that resonates more with traditional uses of bagpipes in ceremonial or somber contexts. Rather than imitating the screeches of an electric guitar with the bagpipes, McCartney emulates a sweet folky lullaby that plays upon the origins of the instrument. The pipes are played softly to soothe, as could be expected of a typical Highland tune.

“Dead” by Korn is its own beast entirely. In the 1999 track, the dissonant wail of the bagpipe is accompanied by eerie whispers of “all I want in life is to be happy.” At only one minute and 12 seconds long, the lament remains relatively monotonous throughout, merely repeating lyrics except for twice when lead singer Jonathan Davis sings, “It seems funny to me / How fucked things can be” and “Every time I get ahead / I feel more dead.” The screeches of the bagpipes invoke an eerie and distant cry that almost muddles the overlaid lyrics. In this instance, the ‘pipes kindle the same sentiments as a funeral procession, evoking another historical use of the bagpipe. Korn thus bridges the orthodox and unorthodox. The use of bagpipes by a heavy metal band strongly contradicts the provincial tradition of the instrument, even though its sorrowful tone in “Dead” nods to the instruments’ historical use. Korn flaunts its classic jarring vocals and buttresses their strident nature with the distant screech of the ‘pipes, resulting in a compelling dichotomy of style and gripping complement of flavor.

Bagpipes’ thorny and extensive history makes them all the more poignant when they rear their heads during a piece. The pipes are an instrument that demand attention, loudly announcing their presence even when merely accompanying overlaying vocals or other instrumentation. While their practicality and use have relegated their appearance to solely cultural contexts, bagpipery surged throughout the musical sphere as a test of rock's bounds. As ‘70s and ‘80s rock bands took their cultural instruments to the stage, they opened the door behind them for a surge in unconventional instruments in a genre defined by its musical reliability. Rock music soared with the promise of riveting guitar solos and voice-shattering vocals, and introducing instruments such as the bagpipes, sitar, and the theremin within the scene by other artists added layers to that promise. While the ‘70s and ‘80s would certainly not be the last time that artists would introduce unconventional means to invoke somber or rustic tones in their music, what began in this era transcends time. Artists today are still grappling with ways to switch up melodies and beats with wacky vocals, new rhythms, and, of course, instruments one would never expect.