Songs of Protest: Declan McKenna’s “Brazil” Criticizes FIFA and Brazilian Leaders

During preparations for the 2014 World Cup in São Paulo, Brazilians faced a harsh reality: their leaders’ loyalty to their country’s beloved sport overshadowed the needs of their own citizens.

Music is one of society’s best teachers. In Songs of Protest, writers analyze some of music’s greatest hits, using their findings to make sense of the world around them.

Written by Katy Vanatsky

Photo courtesy of Big Fenomeno

Brazilian soccer legend Edson Arantes do Nascimiento, most commonly known as Pelé, once said, “Brazil eats, sleeps, and drinks football! It lives football!” However, as echoed in Declan McKenna’s 2015 indie hit “Brazil,” this playful metaphor became painfully real as Brazilian citizens’ needs were cast aside in preparation for the 2014 FIFA World Cup.

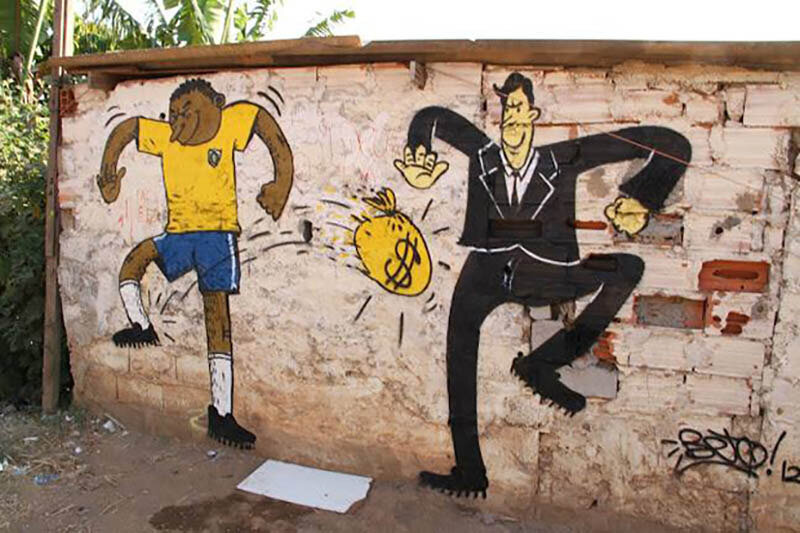

Soccer is an extremely important aspect of Brazil’s culture and national identity, the only country whose team has participated in every World Cup hosted. In Brazil, soccer is not only a sport but a form of creative expression, an artform introduced to children as soon as they learn to walk. In the bridge of “Brazil,” McKenna sings, “Everyone plays the beautiful game while out in Brazil,” in reference to a term for the sport popularized by Pelé, highlighting the game’s almost sacred status in Brazilian culture. However, McKenna’s “Brazil” mainly emphasizes the striking differences in lifestyle between the wealthy Brazilian officials and FIFA executives who made the decision to host the event in São Paulo, versus the millions of vulnerable Brazilians who were harmed by their decision.

In 2013, amidst widespread protests calling for higher wages and improvements to public education, health, and transportation, Brazil spent an estimated $11.63 billion to put on the World Cup — roughly equal to the amount spent on Bolsa Familia that same year. Equating the two’s budget, one being a sports entertainment competition and the other Brazil’s social welfare program that supports over 50 million people, proves sobering. In his second verse, McKenna sings, “I know you can’t eat leather, but you can’t stop me,” referring to the traditionally leather skin of a soccer ball. In a country where over 26% of citizens live below the poverty line, and 8.5% live on less than $45 a month, the World Cup was taking food out of its peoples’ mouths.

Photo courtesy of Andre Penner

The project, however, was allocated more than just a lofty budget. The building and renovations of stadiums, airports, roads, and other infrastructure to support the massive influx of soccer fans into São Paulo required the forced removal of around 170,000 Brazilians from their homes. Some of these citizens were then forcibly resettled into huts without electricity or running water.

After facing this hardship, impoverished Brazilian citizens were unable to reap any meager economic benefits from the event, since the sale of food, drinks, and souvenirs outside of stadiums was restricted to licensed vendors: paid sponsors of FIFA. Promises that the World Cup would uplift the Brazilian economy fell short due to the extensive greed and corruption of the organization, causing many Brazilians to feel lied to: “Why would you lie? Why would you lie about how you feel?”

The song’s chorus doesn’t pull punches either; McKenna describes the lifestyle of an unnamed man as he sings, “I heard he lives down the river somewhere with six cars and a grizzly bear.” These lines are likely in reference to Sepp Blatter, the former FIFA president who served in the role for 17 consecutive years, and owns a luxury watch collection valued at over $400,000, among other riches. Mckenna continues, “He’s got eyes, but he can’t see / Well he talks like an angel, but he looks like me.” Blatter, along with the other high-ranking FIFA and Brazilian officials, had an almost other-worldly authority over Brazilian’s livelihoods when making plans for the 2014 World Cup. But instead of using this authority to support the Brazilian people, they chose to be selectively blind to their needs.“I’ve got a mission and my mission is real,” McKenna sings in the second verse. In a 2017 interview with Face Culture, McKenna said that his main goal of the song was to “hopefully make people think a little bit” and to get them more engaged with the issues he addresses in “Brazil.”

FIFA’s epidemic of corruption that McKenna aimed to unveil was finally brought to light in 2015. The corruption scandal resulted in the impeachment of Sepp Blatter and the arrest of 6 other FIFA executives by the Swiss police on charges of racketeering, wire fraud, and money laundering. But aside from the damages resulting from the 2014 World Cup, “Brazil” calls to a broader issue: to what extent is a host nation responsible for protecting its more vulnerable citizens from potential harm? This question becomes even more relevant this year as Japan moves forward with plans to host the Olympic games in Tokyo amid a global pandemic. While the movement McKenna’s “Brazil” was a part of resulted in major consequences for FIFA, world sports organizations either didn’t learn their lesson or simply don’t care, as the International Olympic Committee continues to force the games on an unwilling Japanese public who will ultimately bear the cost of that decision, just as Brazil does today.