The Evolution of Jazz Album Covers

A look at what makes a jazz album cover and how the visual style of jazz cover art was created.

Written by Mark Yoder

In 1939, 78 rpm records, which only played one song per side, were packaged in brown paper sleeves. The only signifier of an artist’s work was their name stamped in black or gold ink, making albums essentially indistinguishable from one another. But, the first-ever art director of Columbia Records, Alex Steinweiss, saw an opportunity to creatively reflect the content of the music in an eye-catching way — thus, the album cover was born.

Image courtesy of Concord Music

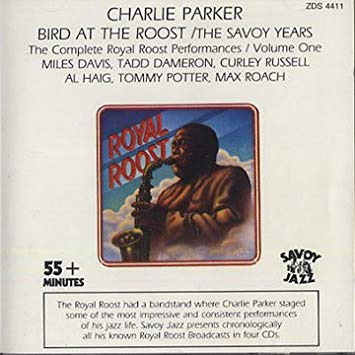

The early years of the album cover offered a unique challenge to designers everywhere to create an accurate visualization of the music. The early ‘40s were also a time when jazz was continuing to grow and evolve as a genre, moving away from the easy-to-dance-to big band swing and towards the freer and more musically complex bebop. Charlie Parker was one of the prominent figures in this style and was an innovator in the jazz genre.

However, the album cover design for his album, Bird at the Roost, created by Dick Smith, did not come close to matching Parker’s level of creativity and intensity. All of the necessary information is there — artist, album, features, length, a small illustration of Parker on sax is framed at the center of the cover — but it doesn’t look like jazz. Its symmetry and lack of variation make it feel more like a textbook cover or a museum brochure, which is the opposite of what bebop was about.

While Steinweiss was figuring out how to improve record packages, German-born American jazz enthusiast Alfred Lion was trying to found a new jazz label called Blue Note that cultivated experimentation and creativity by giving its artists the room to operate. Lion meticulously searched for the most innovative and talented creatives to bring Blue Note to the mainstream. He was an advocate of expression and let the artists create how and what they wanted to create.

Images courtesy of Universal Music Group

This philosophy is clear in these two album covers designed by John Hermansader, a designer recruited by Lion. While they are somewhat rough around the edges, such as the wonky font used on the left or the loose penmanship used on the right, the bold monochromatic color schemes creatively integrate with imagery and type, showing the energy of the albums and the labels.

Images courtesy of Universal Music Group

In 1955, a young Chicagoan designer named Reid Miles was appointed art director of Blue Note and was tasked with creating 12” cover designs for the entire Blue Note catalog — over 500 album covers. It is interesting to view Miles’s art in relation to some of Blue Note’s earlier album covers, specifically how he was able to refine and evolve on the work of Hermansader.

Miles continued the distinct monochromatic treatment, but where these covers truly shine is the creatively-integrated type on top of the photograph. Dexter Gordon’s saxophone became a perfect framing device for the text on A Swingin’ Affair. Hank Mobley smokes a cigarette while being framed by something metal and circular in the foreground of the image, a clever nod to the album title, No Room for Squares. Even further, the title has been framed by a square in the top left corner. The creativity and perfect marriage between music, fonts, and imagery make these albums so completely timeless and iconic.

Blue Note and Reid Miles were very early in elevating the concept of an album cover because they treated them as more than just an informative label or a fun package, but as their own unique art piece that could be perfectly paired with the music within. Reid Miles is given most of the credit for the fame of the Blue Note artwork and his talent and imagination is clear, but credit should also be distributed to photographer Frank Wolff and Hermansader for laying the groundwork of the label.

Image courtesy of Trio Records

Image courtesy of GAD Records

The records from Blue Note — after being widely circulated — defined the visual style of jazz around the world for decades to come. The artwork for the two albums above show this global influence. Scenery, released in 1976 by Japanese pianist Ryo Fukui, as well as Meets Studio M-2 by the Polish Jazz Quartet contain all of the elements of the Blue Note style: vivid color choices, dynamic layout, and text placement. The way the profile of Fukui has been cropped in and then placed to the right to make room for the large vertical title text on the left is very reminiscent of the bold layout choices used by Blue Note. The art for Meets Studio M-2 uses an italicized serif font and creatively cropped images of the musicians with their instruments placed in monochromatic boxes. Such stylistic choices are clearly influenced by Blue Note’s previous artwork.

Image courtesy of Spotify

Image courtesy of Tuba Records

The life of this graphic style has even gone beyond the jazz genre. Spotify frequently uses a one or two color treatment in the designs of their advertisements and playlist cover images such as in the monochromatic image of Schoolboy Q used for the widely popular RapCaviar playlist. The style also seems to emulated by various current album artwork, such as in Cinematronics by Norwegian electronica project Ugress. The design has the same monochromatic color scheme with an image that is cropped in to make room for type.

Alex Steinweiss realized how effective it could be to create artwork to go on the sleeves of records. Then, the creative team at Blue Note took his idea and expanded on it by creating highly expressive and captivating designs that could stand as pieces of art in their own right. While the album cover of 2019 is not the same as the album cover of 1955, people still see the album cover before they hear the album. Not utilizing them as yet another vehicle of expression is a missed opportunity.